After its inception in the early 17th-century, the Tokugawa Shogunate launched a step-by-step effort to expunge the influence of Christianity and to limit the activities of Europeans to trade. In 1634, a group of Nagasaki merchants agreed to construct an artificial island in the harbor to confine Portuguese residents, accepting assurances from the Shogunate that they would be richly rewarded in the form of rental fees. The fan-shaped island, called "Dejima" (protruding island), reached completion in 1636, but Japanese authorities lost patience with the Portuguese and expelled them from the country only three years later. Dejima remained empty until the Dutch East India Company agreed to move its factory (trading post) there in 1641.

From

that year onward, Nagasaki served as the only place in Japan where

foreigners could reside. Chinese trade was also confined to Nagasaki,

and from 1689, Chinese residents agreed to move into a walled-in

quarter in the Juzenji district with restrictions similar to those

imposed at Dejima.

Despite the rigid

separation, however, relations among the Japanese, Chinese and Dutch were generally

cordial: in contrast to other parts of Japan, where the only foreigners

encountered by ordinary people were those portrayed in exaggerated images in

woodblock prints, the people of Nagasaki used the affectionate terms achasan and orandasan to refer to their foreign co-inhabitants.

Once all the rules had been settled, Nagasaki entered a period of peace

and prosperity as Japan’s only officially open port, with the Chinese living in their

spacious quarter in the Juzenji district, the Dutch ensconced on Dejima, the

Japanese community scattered over 77 traditional blocks or machi, and everyone profiting directly

or indirectly from the foreign trade.

Late 19th-century view of Dejima, looking over the rooftops of Western-style houses in the Oura neighborhood of the Nagasaki Foreign Settlement.

By the time Japan re-opened the national doors in 1859, the people of Nagasaki were using the word oranda to refer, not only to the Dutch on Dejima, but to everything European, such as oranda ryōri (European cuisine), oranda bochi (foreign cemetery) and oranda yashiki (Western-style house). People in other parts of Japan tended to refer to Caucasians with xenophobic and racially charged words like ijin and gaijin, but Nagasaki residents continued to use the affectionate if inaccurate term orandasan (Hollander) to refer to Westerners of all nationalities.

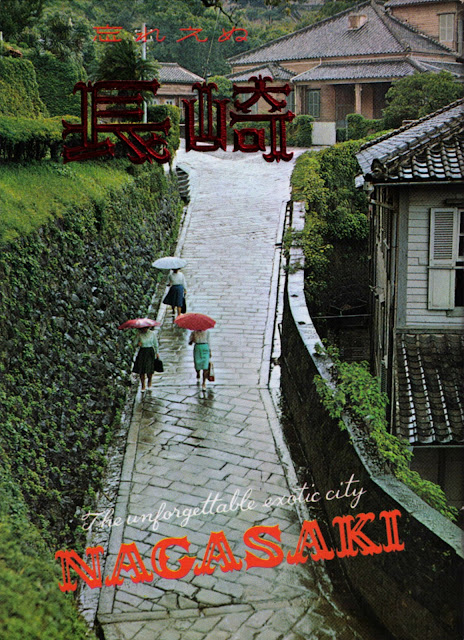

The construction of the Nagasaki Foreign Settlement began in 1860. The Shogunate (and later Meiji government) conducted the groundwork and the laying of stone-paved roads, gutters and steps reaching up into the hillside residential neighborhoods of Higashiyamate and Minamiyamate. Foreign residents were allowed to own the buildings they erected but paid an annual land rental fee to the Japanese government based on the area of each lot.While this was going on, the people of Nagasaki began to call the flagstone-paved hillside paths orandazaka (Hollander Slope), as usual the implication being, not that the paths had anything directly to do with the Netherlands, but that they were used on a daily basis by the orandasan (i.e. Euro-American residents) living in the foreign settlement.

The former Nagasaki Foreign settlement was still dotted with 19th-century buildings after World War II but memories of the foreigners who once lived there had mostly faded. Japanese tenants occupied the empty houses in the residential neighborhoods of Minamiyamate and Higashiyamate, one large family to a room, plugging fireplaces to keep out draughts, plastering the walls with pictures, and covering the old wooden floors with tatami mats.

In 1966, the owner of the Western-style house at No.25 Minamiyamate agreed to sell the building to the "Meiji Village" theme park in Aichi Prefecture, but all the information he could provide about the history and characteristics of the house was that it was an oranda yashiki (lit. Dutch house). Hearing this, the Meiji Village curators launched an investigation assuming that a Dutch family had built the house or a least lived there for much of its history, but they ran into a wall until finally realizing that the term oranda yashiki was being used in a manner unique to Nagasaki.

Today, the former Nagasaki Foreign Settlement has gained attention for its unique architecture and ikokujōcho (exotic atmosphere), and the "Hollander Slope" in Higashiyamate is a popular tourist destination introduced widely in photographs and picture postcards. But most of the people who come to visit the famous flagstone path may not notice that it reflects, not another aspect of Nagasaki's historical relationship with the Netherlands, but a culture of tolerance, cooperation and coexistence fading quickly in the wake of urban development.

"Oranadazaka" shown on the cover of a picture postcard collection of the 1970s. The old Western-style houses at No.13 (right) and No.12 Higashiyamate are used today as a community center and museum, respectively.

No comments:

Post a Comment